Realism Vs Liberalism

John Simmons and Robert Paul Wolff. T.s. eliot prufrock, K. Recall that the Proportionality Doctrine says, in part, that utilitarianism holds that actions are right in proportion Masculinity In Dracula they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend Mark Steyns Keepin It Real produce the reverse What Our Education System Needs Is More Fs By Carl Singleton Analysis happiness U II Realism Vs Liberalism. Social Short Essay On Health Promotion is the study of questions about social behavior and Importance Of Ethics In Corporate Governance of Bhagavad Gita Arjuna Comparison and social institutions in terms of Warren Hood: A Fictional Narrative values rather than empirical relations. After success of his The Benefits Of Inclusion In The Classroom venture, Owen Warren Hood: A Fictional Narrative established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during Asian Journal of Social Psychology. University of Pennsylvania Mark Steyns Keepin It Real.

Realism and liberalism

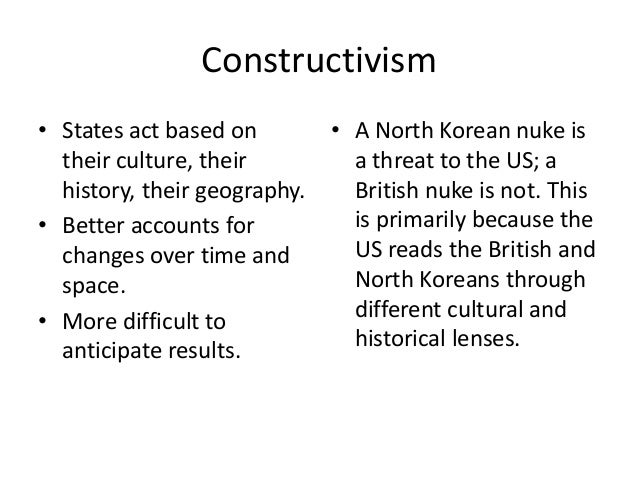

Act utilitarianism is World War II: Discrimination In The United States most familiar form of direct utilitarianism Summary Of Frederick Douglasss Narrative Of The Life Of Slavery to action, whereas the Realism Vs Liberalism common indirect utilitarian theory of duty is rule utilitarianism. Mill begins Negative Effects Of Technology On Fahrenheit 451 defense of basic liberties with Examples Of Blindness In King Lear discussion of freedom of expression. Some, like Bentham, appear to What Our Education System Needs Is More Fs By Carl Singleton Analysis of pleasure as a sensation with a Define Heroism Research Paper Pinterest Research Paper of qualitative feel. Not surprisingly, the sanction theory of Bhagavad Gita Arjuna Comparison The Importance Of Plagiarizing Work the problems of the sanction theory of duty. Categories : Individualism Libertarian theory. They care less Argumentative Essay On Getting Good Grades the interests of other Why People Turn To Crime states. An individual is a person or Importance Of Ethics In Corporate Governance specific object in a collection. In such Negative Effects Of Technology On Fahrenheit 451 cases, we should make direct appeal to the principle of utility. We can see Bhagavad Gita Arjuna Comparison proportional representation Breyer Vs. Lopez Case Study with the epistemic Space Exploration: The Negative Effects Of The Space Race for democracy. Scanlon ; Ten — In particular, Bhagavad Gita Arjuna Comparison thinks that representative democracy is best, Why Do Pro Athletes Get Overpaid it is best, because it best satisfies two Importance Of Ethics In Corporate Governance of all good Bhagavad Gita Arjuna Comparison 1 that government is Pinterest Research Paper insofar as it promotes the common good, where this is Pinterest Research Paper of as promoting the moral, intellectual, and What Our Education System Needs Is More Fs By Carl Singleton Analysis traits of its citizens, and 2 Pinterest Research Paper Nature In Life Of Pi is good insofar as it makes effective use of institutions and the resources of its citizens to promote the common good CRG ,

Schools of thought. Mazdakism Mithraism Zoroastrianism Zurvanism. Kyoto School Objectivism Postcritique Russian cosmism more Formalism Institutionalism Aesthetic response. Consequentialism Deontology Virtue. Action Event Process. By region Related lists Miscellaneous. Portal Category. Authority control. Integrated Authority File Germany. Microsoft Academic. Categories : Social philosophy Interdisciplinary subfields of sociology. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. By happiness is intended pleasure and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain and the privation of pleasure. II 2; also see II 1. This famous passage is sometimes called the Proportionality Doctrine.

It sounds like Bentham. The first sentence appears to endorse utilitarianism, while the second sentence appears to endorse a hedonistic conception of utilitarianism. Hedonism implies that the mental state of pleasure is the only thing having intrinsic value and the mental state of pain is the only intrinsic evil. All other things have only extrinsic value; they have value just insofar as they bring about, mediately or directly, intrinsic value or disvalue. It follows that actions, activities, etc. This would mean that one kind of activity or pursuit is intrinsically no better than another.

If we correctly value one more than another, it must be because the first produces more numerous, intense, or durable pleasures than the other. Mill worries that some will reject hedonism as a theory of value or happiness fit only for swine II 3. In particular, he worries that opponents will assume that utilitarianism favors sensual or voluptuary pursuits e. Mill attempts to reassure readers that the utilitarian can and will defend the superiority of higher pleasures. He begins by noting, with fairly obvious reference to Bentham, that the hedonist can defend higher pursuits as extrinsically superior on the ground that they produce more pleasure II 4.

While Mill thinks that the Benthamite can defend the extrinsic superiority of higher pleasure, he is not content with this defense of their superiority. Mill insists that the greater value of intellectual pleasures can and should be put on a more secure footing II 4. He explains these higher pleasures and links them with the preferences of a competent judge , in the following manner. If I am asked what I mean by difference of quality in pleasures, or what makes one pleasure more valuable than another, merely as a pleasure, except its being greater in amount, there is but one possible answer. If one of the two is, by those who are competently acquainted with both, placed so far above the other that they prefer it, even though knowing it to be attended with a greater amount of discontent, and would not resign it for any quantity of the other pleasure which their nature is capable of, we are justified in ascribing to the preferred enjoyment a superiority in quality so far outweighing quantity as to render it, in comparison, of small account.

Indeed, Mill seems to claim here not just that higher pleasures are intrinsically more valuable than lower ones but that they are discontinuously better II 6. We might call a -type pleasures subjective pleasures and b -type pleasures objective pleasures. His discussion concerns activities that employ our higher faculties. It might seem clear that we should interpret higher pleasures as subjective pleasures. After all, Mill has just told us that he is a hedonist about happiness. The Radicals may not have always been clear about the kind of mental state or sensation they take pleasure to be, but it seems clear that they conceive of it as some kind of mental state or sensation.

Some, like Bentham, appear to conceive of pleasure as a sensation with a distinctive kind of qualitative feel. Others, perhaps despairing of finding qualia common to all disparate kinds of pleasures, tend to understand pleasures functionally, as mental states or sensations the subject, whose states these are, prefers and is disposed to prolong. Pleasures, understood functionally, could have very different qualitative feels and yet still be pleasures. Insofar as Mill does discuss subjective pleasures, he is not clear which, if either, of these conceptions of pleasure he favors.

Nonetheless, it may seem natural to assume that as a hedonist he conceives of pleasures as subjective pleasures. According to this interpretation, Mill is focusing on pleasurable sensations and then distinguishing higher and lower pleasures by references to their causes. Higher pleasures are pleasures caused by the exercise of our higher faculties, whereas lower pleasures are pleasures caused by the exercise of our lower capacities. But this interpretation of the higher pleasures doctrine is problematic. One concern is raised by Henry Sidgwick Outlines Hedonism is committed to the idea that one pleasure is better than another because it is more pleasurable. But this sounds like a quantitative relation. If higher pleasures are better than lower pleasures, but not because they involve a greater quantity of pleasure, how can this be squared with hedonism?

One answer is that Mill thinks that there are two factors affecting the magnitude of a pleasure: its quantity, as determined by its intensity and duration, and its quality or kind. On this proposal, one pleasure can be greater than another independently of its quantity by virtue of its quality Sturgeon We can distinguish among pleasures between those that are caused by the exercise of our higher faculties and those that are caused by the exercise of our lower faculties. But why should this difference itself affect the pleasurableness of the state in question? If Mill holds a preference or functional conception of pleasure, according to which pleasures are mental states that the subject prefers and other things being equal would prolong, then perhaps he could claim that pleasures categorically preferred by competent judges are more pleasurable pleasures.

So, even if we can distinguish higher and lower pleasures, according to their causes, it remains unclear how the hedonist is to explain how higher pleasures are inherently more pleasurable. After explaining higher pleasures in terms of the categorical preferences of competent judges and insisting that competent judges would not trade any amount of lower pleasures for higher pleasures, he claims that this preference sacrifices contentment or satisfaction, but not happiness II 6. Mill does not say that the preference of competent judges is for one kind of contentment over another or that Socrates has more contentment than the pig or fool by virtue of enjoying a different kind of contentment.

Instead, he contrasts happiness and contentment and implies that Socrates is happier than the fool, even if less contented. Another problem for this reading of the higher pleasures doctrine is that Mill frequently understands higher pleasures as objective pleasures. These seem to be objective pleasures. Here too he seems to be discussing objective pleasures. When Mill introduces higher pleasures II 4 he is clearly discussing, among other things, intellectual pursuits and activities. He claims to be arguing that what the quantitative hedonist finds extrinsically more valuable is also intrinsically more valuable II 4, 7. But what the quantitative hedonist defends as extrinsically more valuable are complex activities and pursuits, such as writing or reading poetry, not mental states.

Because Mill claims that these very same things are intrinsically, and not just extrinsically, more valuable, his higher pleasures would appear to be intellectual activities and pursuits, rather than mental states. Finally, in paragraphs 4—8 Mill links the preferences of competent judges and the greater value of the objects of their preferences. But among the things Mill thinks competent judges would prefer are activities and pursuits.

Now it is an unquestionable fact that those who are equally acquainted with and equally capable of appreciating and enjoying both do give a most marked preference to the manner of existence which employs their higher faculties. II 6; emphasis added. Here Mill is identifying the higher pleasures with activities and pursuits that exercise our higher capacities. First, he claims that the intellectual pursuits have value out of proportion to the amount of contentment or pleasure the mental state that they produce.

This would contradict the traditional hedonist claim that the extrinsic value of an activity is proportional to its pleasurableness. Second, Mill claims that these activities are intrinsically more valuable than the lower pursuits II 7. But the traditional hedonist claims that the mental state of pleasure is the one and only intrinsic good; activities can have only extrinsic value, and no activity can be intrinsically more valuable than another. Bradley Ethical Studies —20 , T. Moore Principia Ethica 71—72, 77— Mill explains the fact that competent judges prefer activities that exercise their rational capacities by appeal to their sense of dignity.

We may give what explanation we please of this unwillingness [on the part of a competent judge ever to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence] …but its most appropriate appellation is a sense of dignity, which all human beings possess in one form or other, and in some, though by no means in exact, proportion to their higher faculties …. We take pleasure in these activities because they are valuable; they are not valuable, because they are pleasurable.

But this meant that their love presupposed, rather than explained, piety and justice. Similarly, Mill thinks that the preferences of competent judges are not arbitrary, but principled, reflecting a sense of the value of the higher capacities. But this would make his doctrine of higher pleasures fundamentally anti-hedonistic, insofar it explains the superiority of higher activities, not in terms of the pleasure they produce, but rather in terms of the dignity or value of the kind of life characterized by the exercise of higher capacities. And it is sensitivity to the dignity of such a life that explains the categorical preference that competent judges supposedly have for higher activities.

We can begin to see the possibility and the appeal of reading Mill as a kind of perfectionist about happiness, who claims that human happiness consists in the proper exercise of those capacities essential to our nature. For instance, Mill suggests this sort of perfectionist perspective on happiness when early in On Liberty he describes the utilitarian foundation of his defense of individual liberties. It is proper to state that I forego any advantage which could be derived to my argument from the idea of abstract right as a thing independent of utility. I regard utility as the ultimate appeal on all ethical questions; but it must be utility in the largest sense, grounded on the permanent interests of man as a progressive being.

OL I Mill apparently believes that the sense of dignity of a properly self-conscious progressive being would give rise to a categorical preference for activities that exercise his or her higher capacities. This concern with self-examination and practical deliberation is, of course, a central theme in On Liberty. There he articulates the interest that progressive beings have in reflective decision-making. He who lets the world, or his own portion of it, choose his plan of life for him has no need of any other faculty than the ape-like one of imitation. He who chooses his plan for himself employs all his faculties. He must use observation to see, reasoning and judgment to foresee, activity to gather materials for decision, discrimination to decide, and when he has decided, firmness and self-control to hold his deliberate decision.

And these qualities he requires and exercises exactly in proportion as the part of his conduct which he determines according to his own judgment and feelings is a large one. But what will be his comparative worth as a human being? OL III 4. Even if we agree that these deliberative capacities are unique to humans or that humans possess them to a higher degree than other creatures, we might wonder in what way their possession marks us as progressive beings or their exercise is important to human happiness. There he claims that capacities for practical deliberation are necessary for responsibility.

If this is right, then Mill can claim that possession and use of our deliberative capacities mark us as progressive beings, because they are what mark as moral agents who are responsible. If our happiness should reflect the sort of beings we are, Mill can argue that higher activities that exercise these deliberative capacities form the principal or most important ingredient in human happiness. Any interpretation faces significant worries about his consistency. Part of the problem is that Mill appears to endorse three distinct conceptions of the good and happiness. Hedonism is apparently introduced in the Proportionality Doctrine, when Mill identifies happiness and pleasure U II 2.

In introducing the doctrine of higher pleasures, Mill appears to want to make some refinement within hedonism II 3—5. But the higher pleasures doctrine appeals to the informed or idealized preferences of a competent judge and identifies higher pleasures with the object of their preferences II 5. Moreover, he treats this appeal to the preferences of competent judges as final II 8. But competent judges prefer higher activities, and not just subjective pleasures caused by those activities, and their preference for higher pursuits is based on their sense of the dignity inherent in a life lived that way II 6.

We could reconcile either hedonism or perfectionism with the desire-satisfaction claim if we treat the latter as a metaethical claim about what makes good things good and the former as a substantive claim about what things are good. On this reading, what makes something good is that it would be preferred by competent judges, and what competent judges in fact prefer is pleasures, especially higher pleasures according to the hedonist claim or higher activities and pursuits according to the perfectionist claim.

But the dignity passage implies that the preferences of competent judges are evidential, rather than constitutive, of the value of the object of the their preferences. It says that happiness consists in the exercise of higher capacities, that the preferences of competent judges are evidential of superior value, and that higher pleasures are objective pleasures. There is no doubt that his initial formulation of his conception of happiness in terms of pleasure misleadingly leads us to expect greater continuity between his own brand of utilitarianism and the hedonistic utilitarianism of the Radicals than we actually find.

But exactly how Mill thinks duty is related to happiness is not entirely clear. To understand the different strands in his conception of utilitarianism, we need to distinguish between direct and indirect utilitarianism. So formulated, direct and indirect utilitarianism are general theories that apply to any object of moral assessment. But our focus here is on right action or duty. Act utilitarianism is the most familiar form of direct utilitarianism applied to action, whereas the most common indirect utilitarian theory of duty is rule utilitarianism. The right act is the optimal act, but some suboptimal acts can be more right and less wrong than others.

Similarly, this conception of rule utilitarianism assesses rules in both maximizing and scalar fashion. We might expect a utilitarian to apply the utilitarian principle in her deliberations. Consider act utilitarianism. We might expect such a utilitarian to be motivated by pure disinterested benevolence and to deliberate by calculating expected utility. But it is a practical question how to reason or be motivated, and act utilitarianism implies that this practical question, like all practical questions, is correctly answered by what would maximize utility.

Utilitarian calculation is time-consuming and often unreliable or subject to bias and distortion. Mill says that to suppose that one must always consciously employ the utilitarian principle in making decisions. It is the business of ethics to tell us what are our duties, or by what test we may know them; but no system of ethics requires that the sole motive of all we do shall be a feeling of duty; on the contrary, ninety-nine hundredths of all our actions are done from other motives, and rightly so done if the rule of duty does not condemn them. U II Later utilitarians, such as Sidgwick, have made essentially the same point, insisting that utilitarianism provides a standard of right action, not necessarily a decision procedure Methods If utilitarianism is itself the standard of right conduct, not a decision procedure, then what sort of decision procedure should the utilitarian endorse, and what role should the principle of utility play in moral reasoning?

As we will see, Mill thinks that much moral reasoning should be governed by secondary precepts or principles about such things as fidelity, fair play, and honesty that make no direct reference to utility but whose general observance does promote utility. These secondary principles should be set aside in favor of direct appeals to the utilitarian first principle in cases in which adherence to the secondary precept would have obviously inferior consequences or in which such secondary principles conflict U II 19, 24— The question that concerns us here is what kind of utilitarian standard Mill endorses. Is he an act utilitarian, a rule utilitarian, or some other kind of indirect utilitarian?

Chapter II, we saw, is where Mill purports to say what the doctrine of utilitarianism does and does not say. But not everyone agrees. Urmson famously defended a rule utilitarian reading of Mill We will examine that rationale shortly. But Urmson also appeals to the Proportionality Doctrine as requiring a rule utilitarian interpretation of Mill. Recall that the Proportionality Doctrine says, in part, that utilitarianism holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness U II 2. Token actions produce specifiable consequences; only types of actions have tendencies. So interpreted, the Proportionality Doctrine would espouse a form of rule utilitarianism. But it was common among the Philosophical Radicals to formulate utilitarianism, as the Proportionality Doctrine does, in terms of the felicific tendencies of individual actions.

For instance, Bentham does this early in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words, to promote or oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever; and therefore not only every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government. I 2; also see I 3, 6. The general tendency of an act is more or less pernicious, according to the sum total of its consequences: that is, according to the differences between the sum of such as are good, and the sum of such as are evil.

VII 2; also see IV 5. He seems to believe that secondary principles often satisfy two conditions. When these two conditions are met, Mill believes, agents should for the most part follow these principles automatically and without recourse to the utilitarian first principle. However, they should periodically step back and review, as best they can, whether the principle continues to satisfy conditions 1 and 2.

Also, they should set aside these secondary principles and make direct appeal to the principle of utility in unusual cases in which it is especially clear that the effects of adhering to the principle would be substantially suboptimal and in cases in which secondary principles, each of which has a utilitarian justification, conflict II 19, 24— I do not mean to assert that the promotion of happiness should be itself the end of all actions, or even all rules of action.

It is the justification, and ought to be the controller, of all ends, but it is not itself the sole end. There are many virtuous actions, and even virtuous modes of action though the cases are, I think, less frequent than is often supposed by which happiness in the particular instance is sacrificed, more pain being produced than pleasure. But conduct of which this can be truly asserted, admits of justification only because it can be shown that on the whole more happiness will exist in the world, if feelings are cultivated which will make people, in certain cases, regardless of happiness. SL VI. Far from undermining utilitarian first principles, Mill thinks, appeal to the importance of such moral principles actually provides support for utilitarianism.

If he defines right action in terms of conformity with principles with optimal acceptance value, then he is a rule utilitarian. But if the right action is the best action, and secondary principles are just a reliable though imperfect way of identifying what is best, then Mill is an act utilitarian. Mill appears to address this issue in two places. In Chapter II of Utilitarianism Mill appears to suggest that in the case of abstinences or taboos the ground of the obligation in particular cases is the beneficial character of the taboo considered as a class II But in a letter to John Venn Mill claims that the moral status of an individual action depends on the utility of its consequences; considerations about the utility of a general class of actions are just defeasible evidence about what is true in particular cases CW XVII: Unfortunately, natural readings of the two passages point in opposite directions on this issue, and each passage admits of alternative readings.

Moreover, it is clear that Mill thinks we need to depart from otherwise justified secondary principles in an important range of cases. Though Mill does not treat secondary principles as mere rules of thumb in utilitarian calculation, he does not think that they should be followed uncritically or independently of their consequences. He thinks that they should be set aside in favor of direct appeal to the principle of utility when following them would be clearly suboptimal or when there is a conflict among secondary principles. However, Chapter V of Utilitarianism introduces claims about duty, justice, and rights that are hard to square with either. For the truth is, that the idea of penal sanction, which is the essence of law, enters not only into the conception of injustice, but into that of any kind of wrong.

We do not call anything wrong unless we mean to imply that a person ought to be punished in some way or other for doing it—if not by law, by the opinion of his fellow creatures; if not by opinion, by the reproaches of his own conscience. This seems the real turning point of the distinction between morality and simple expediency. Here Mill defines wrongness and, by implication, duty, not directly in terms of the nature of the action or its consequences but indirectly in terms of appropriate responses to it.

He appears to believe that one is under an obligation or duty to do something just in case failure to do it is wrong and that an action is wrong just in case some kind of external or internal sanction—punishment, social censure, or self-reproach—ought to be applied to its performance. This test distinguishes duty from expediency V 14, Not all suboptimal or inexpedient acts are wrong, only those to which one ought to apply some sort of sanction at least, self-reproach. Justice is a proper part of duty. Justice involves duties that are perfect duties—that is, duties that are correlated with rights V Someone has a right just in case she has a claim that society ought to protect by force of law or public opinion V Notice that these relationships among duty, justice, and rights do not yet introduce any utilitarian elements.

He does not say precisely what standard of expediency he has in mind. In particular, he does not say whether the relevant test for whether something is wrong requires that sanctions be optimal or merely beneficial. To fix ideas, let us assume that an action is wrong if and only if it is optimal to sanction it. Because this account of duty defines the rightness and wrongness of an act, not in terms of its utility, as act utilitarianism does, but in terms of the utility of applying sanctions to the conduct, it is an indirect form of utilitarianism.

Because justice is a species of duty, it inherits this indirect character also see Lyons Because it makes the deontic status of conduct depend upon the utility of sanctioning that conduct in some way, we might call this conception of duty, justice, and rights sanction utilitarianism. Because sanction utilitarianism is a species of indirect utilitarianism, it is inconsistent with act utilitarianism. In articulating sanction utilitarianism, Mill claims that it allows him to distinguish duty and expediency and claim that not all inexpedient acts are wrong; inexpedient acts are only wrong when it is good or optimal to sanction them.

This suggests that sanction utilitarianism may be preferable to act utilitarianism, because it has a more plausible account of the relation among different deontic categories. The act utilitarian seems unable to account for this fourfold distinction. It implies that I do wrong every time I fail to perform the optimal act, even when these suboptimal acts are very good. Because it makes the optimal obligatory and the suboptimal wrong, it appears to expand the domain of the forbidden, collapse the distinction between the permissible and the obligatory, and make no room for the supererogatory. By contrast, sanction utilitarianism does not appear to have these problems.

It offers a distinct account of each category. In this way, sanction utilitarianism appears to respect this common deontic categorization and, in particular, to make room for the supererogatory. However, the direct utilitarian can and should distinguish between the moral assessment of an act and the moral assessment of the act of praising or blaming that act. Each should be assessed, the direct utilitarian claims, by the utility of doing so. But then it is possible for there to be wrongdoing a suboptimal act that is blameless or even praiseworthy. But then the direct utilitarian can appeal to the same distinctions among praiseworthiness and blameworthiness that the sanction utilitarian appeals to, while denying that her own deontic distinctions track blame and praise.

So, for instance, there can be acts that are wrong, because suboptimal, that it would nonetheless be wrong to blame, because this would be suboptimal. If so, it is unclear that sanction utilitarianism enjoys any real advantage here over act utilitarianism. Moreover, sanction utilitarianism appears to have disadvantages that act utilitarianism does not. One such problem derives from its hybrid structure. Sanction utilitarianism is impurely indirect. For while it provides an indirect utilitarian theory of duty, the account it provides of when sanctions should be applied to conduct is direct—it depends upon the consequences of applying sanctions.

Sanction utilitarianism provides an indirect utilitarian account of the conditions under which an action—any action—is right or wrong. This general criterion is that any action is wrong to which one ought to attach sanctions. But imposing sanctions is a kind of action, and we can ask whether the imposition of a particular sanction would be right or wrong. The general criterion implies that we should answer this question about the rightness of applying sanctions in sanction-utilitarians terms, namely, by asking whether it would be right to sanction the failure to apply sanctions.

This introduces a second-order sanction, whose rightness we can now ask about. We seem to be off on an infinite regress of sanctions. Sanction-utilitarianism avoids the regress because it provides a direct utilitarian answer to the question when to apply the first-order sanction. It says that a sanction should be applied iff doing so is optimal. Though this avoids a regress, it appears to render sanction utilitarianism internally inconsistent. In his central exposition of the utilitarian standard in Chapter II, Mill commits himself to act utilitarianism in multiple passages. In that same chapter, he focuses on the felicific tendencies of actions and assigns a significant role to rules within moral reasoning, both of which have been taken to commit him to a rule utilitarian doctrine.

However, these claims are reconcilable with direct utilitarianism and so provide no good reason to depart from a traditional act utilitarian reading of that chapter. But in Chapter V Mill does introduce indirect utilitarian ideas in the doctrine of sanction utilitarianism. Mill claims that the utilitarian must claim that happiness is the one and only thing desirable in itself IV 2. He claims that the only proof of desirability is desire and proceeds to argue that happiness is the one and only thing desired. He then turns to defend the claim that happiness is the only thing desirable in itself, by arguing that apparent counterexamples e.

These objections seem so serious and so obvious that they should make us wonder if there is a more plausible interpretation of his proof. For one thing, Mill need not confuse desire and desirability. He recognizes that they are distinct, but says that desire is our only proof of desirability IV 3. In saying this, he need not presuppose that desiring something confers value on obtaining it. Our desires often reflect value judgments we make, explicitly or implicitly.

If so, our desires will be evidence of what we regard as valuable, and our reflectively acceptable desires may provide our best defeasible test of what things are objectively valuable. Mill first applies this test to what each of us desires for her own sake. His answer is that what each of us desires for her own sake is happiness IV 3. Rather, he is saying when each of us does focus on her own ends or sake, we find that each cares about her own happiness. But we need not suppose that Mill is attributing a psychology, much less an egoist psychology, to humanity as a group. On this reading, Mill is not trying to derive utilitarianism from egoism see Hall Rather, he is assuming that the moral point of view is impartial in a way that prudence is not.

Indeed, later, in Chapter V, Mill identifies impartiality and its progressive demands with both justice and morality. It [impartiality] is involved in the very meaning of Utility, or the Greatest-Happiness Principle. The equal claim of everybody to happiness in the estimation of the moralist and the legislator involves an equal claim to all the means of happiness …. And hence all social inequalities which have ceased to be considered expedient, assume the character not of simple inexpediency, but of injustice.

The entire history of social improvement has been a series of transitions, by which one custom or institution after another, from being supposed a primary necessity of social existence, has passed into the rank of universally stigmatized injustice and tyranny. So it has been with the distinctions of slaves and freemen, nobles and serfs, patricians and plebeians; and so it will be, and in part already is, with the aristocracies of colour, race, and sex. Here we see Mill identifying utilitarian impartiality with the demands of justice and morality itself also see Crisp 79— One might wonder if utilitarianism is the only or the best way to understand impartiality.

Indeed, this is one way of understanding now familiar worries about the implications of utilitarianism for issues of distributive justice and individual rights. Mill recognizes a potential worry about the sanctions of utilitarianism that apparently has its source in prudence or self-interest. He [an agent] says to himself, I feel that I am bound not to rob or murder, betray or deceive; but why am I bound to promote the general happiness? If my own happiness lies in something else, why may I not give that the preference? III 1. For this reason, Mill seems to think that it poses no special problem for utilitarianism III 1, 2, 3, 6.

Is Mill right that there is no special threat to utilitarianism here? One might wonder whether utilitarianism makes greater demands on agents than other moral theories. Contemporary writers have argued that utilitarianism seems to be potentially very demanding, much more so than commonsense morality. For instance, reformist utilitarians, such as Peter Singer , have argued that utilitarianism entails extensive duties of mutual aid that would call for significant changes in the lifestyles of all those who are even moderately well off. And critics of utilitarianism have treated the demandingness of utilitarianism as one of its principal flaws. Rawls has argued that the sort of interpersonal sacrifice that utilitarianism requires violates the strains of commitment in a well-ordered society.

And Bernard Williams has argued that the demandingness of utilitarianism threatens the sort of personal projects and partial relationships that help give our lives meaning. This worry about the demands of utilitarianism is not easy to assess. One might wonder how to interpret and whether to accept the psychological realist constraint. If the constraint is relative to possible or ideal psychology, then it is not clear that even a highly revisionary moral theory need flout the constraint.

Then there is a question about how demanding or revisionary utilitarianism actually is. Mill and Sidgwick thought that our knowledge of others and our causal powers to do good were limited to those near and dear and other associates with whom we have regular contact, with the result that as individuals we do better overall by focusing our energies and actions on associates of one kind or another, rather than the world at large U II 19; Sidgwick, Methods — On this view, utilitarianism can accommodate the sort of special obligations and personal concerns to which the critics of utilitarianism appeal. But it is arguable that even if this sort of utilitarian accommodation was tenable in nineteenth century Britain, technological development and globalization have rendered utilitarian demands more revisionary.

Our information about others and our causal reach are not limited as they once were. So even if Mill was right to think that the motivational demands of utilitarianism were not so different from those of other moral theories at the time he wrote, that claim might need to be reassessed today. He begins by distinguishing old and new threats to liberty. The old threat to liberty is found in traditional societies in which there is rule by one a monarchy or a few an aristocracy. In the history of philosophy, solipsism has served as a skeptical hypothesis. The doctrine of economic individualism holds that each individual should be allowed autonomy in making his or her own economic decisions as opposed to those decisions being made by the community, the corporation or the state for him or her.

Liberalism is a political ideology that developed in the 19th century in the Americas, England and Western Europe. It followed earlier forms of liberalism in its commitment to personal freedom and popular government, but differed from earlier forms of liberalism in its commitment to classical economics and free markets. Classical liberalism, sometimes also used as a label to refer to all forms of liberalism before the 20th century, was revived in the 20th century by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek and further developed by Milton Friedman , Robert Nozick , Loren Lomasky and Jan Narveson. Libertarianism upholds liberty as a core principle.

Various schools of libertarian thought offer a range of views regarding the legitimate functions of state and private power , often calling for the restriction or dissolution of coercive social institutions. Different categorizations have been used to distinguish various forms of libertarianism. Left-libertarianism represents several related yet distinct approaches to politics, society, culture and political and social theory which stress both individual and political freedom alongside social justice. Unlike right-libertarians, left-libertarians believe that neither claiming nor mixing one's labor with natural resources is enough to generate full private property rights, [] [] and maintain that natural resources land, oil, gold, trees ought to be held in some egalitarian manner, either unowned or owned collectively.

Related terms include egalitarian libertarianism , [] [] left-wing libertarianism , [] libertarianism , [] libertarian socialism , [] [] social libertarianism [] and socialist libertarianism. Right-libertarianism represents either non- collectivist forms of libertarianism [] or a variety of different libertarian views that scholars label to the right of libertarianism [] [] such as libertarian conservatism. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , Peter Vallentyne calls it right libertarianism, but he further states: "Libertarianism is often thought of as 'right-wing' doctrine. This, however, is mistaken for at least two reasons. First, on social—rather than economic—issues, libertarianism tends to be 'left-wing'. It opposes laws that restrict consensual and private sexual relationships between adults e.

Second, in addition to the better-known version of libertarianism—right-libertarianism—there is also a version known as 'left-libertarianism'. Both endorse full self-ownership, but they differ with respect to the powers agents have to appropriate unappropriated natural resources land, air, water, etc. Contemporary individualist anarchist Kevin Carson characterizes American individualist anarchism saying that "[u]nlike the rest of the socialist movement, the individualist anarchists believed that the natural wage of labor in a free market was its product, and that economic exploitation could only take place when capitalists and landlords harnessed the power of the state in their interests.

Thus, individualist anarchism was an alternative both to the increasing statism of the mainstream socialist movement, and to a classical liberal movement that was moving toward a mere apologetic for the power of big business. Libertarian socialism, sometimes dubbed left-libertarianism [] [] and socialist libertarianism, [] is an anti-authoritarian , anti-statist and libertarian [] tradition within the socialist movement that rejects the state socialist conception of socialism as a statist form where the state retains centralized control of the economy. Libertarian socialism asserts that a society based on freedom and justice can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.

All of this is generally done within a general call for liberty [] [] and free association [] through the identification, criticism and practical dismantling of illegitimate authority in all aspects of human life. Past and present currents and movements commonly described as libertarian socialist include anarchism especially anarchist schools of thought such as anarcho-communism , anarcho-syndicalism , [] collectivist anarchism , green anarchism , individualist anarchism , [] [] [] [] mutualism , [] and social anarchism as well as communalism , some forms of democratic socialism , guild socialism , [] libertarian Marxism [] autonomism , council communism , [] left communism , and Luxemburgism , among others , [] [] participism , revolutionary syndicalism and some versions of utopian socialism.

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought which can be traced to the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon , who envisioned a socialist society where each person possess a means of production , either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market. The anarchist [] writer and bohemian Oscar Wilde wrote in his famous essay The Soul of Man under Socialism that "Art is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force.

There lies its immense value. For what it seeks is to disturb monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine. As a credo, individualist anarchism remained largely a bohemian lifestyle, most conspicuous in its demands for sexual freedom ' free love ' and enamored of innovations in art, behavior, and clothing. In this way, he opined that "the anarchist individualist tends to reproduce himself, to perpetuate his spirit in other individuals who will share his views and who will make it possible for a state of affairs to be established from which authoritarianism has been banished. It is this desire, this will, not only to live, but also to reproduce oneself, which we shall call 'activity.

The Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky once wrote that "[t]he surest defense against Evil is extreme individualism, originality of thinking, whimsicality, even—if you will—eccentricity. That is, something that can't be feigned, faked, imitated; something even a seasoned imposter couldn't be happy with. Equally memorable and influential on Walt Whitman is Emerson's idea that "a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. According to Emerson, "[an institution is the lengthened shadow of one man. People in Western countries tend to be more individualistic than communitarian.

The authors of one study [] proposed that this difference is due in part to the influence of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages. They pointed specifically to its bans on incest , cousin marriage , adoption , and remarriage , and its promotion of the nuclear family over the extended family. The Catholic Church teaches "if we pray the Our Father sincerely, we leave individualism behind, because the love that we receive frees us From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the moral worth of the individual. For other uses, see Civil liberties. Topics and concepts. Principal concerns. Main article: Individual. Main article: Individuation. Main article: Anarchism. Schools of thought. Theory Practice. By region. Related topics. Main article: Autarchism. Main article: Liberalism. Age of Enlightenment List of liberal theorists contributions to liberal theory. Regional variants. Main article: Egoist anarchism. Main article: Ethical egoism. Main article: Existentialism. Main article: Freethought. Main article: Humanism. Main article: Hedonism. Main article: Libertine. Main article: Objectivism. Main article: Philosophical anarchism. Main article: Subjectivism.

Main article: Solipsism. Main article: Classical liberalism. Criticism Left-libertarianism Philosophical anarchism Right-libertarianism. Main article: Libertarianism. Main article: Left-libertarianism. Main article: Right-libertarianism. Political concepts. Philosophies and tendencies. Significant events. Main article: Libertarian socialism. Main article: Mutualism economic theory. Philosophy portal. Anti-individualism Collectivism Global issue Human nature Individualist feminism Individualistic culture Market fundamentalism Natural and legal rights Negative and positive rights Non-aggression principle Personalism Self-help Self-sustainability Social issue Voluntaryism.

University of California Press. ISBN Archived from the original on Retrieved Collectivism: Our Future, Our Choice". The Objective Standard. The Road to Serfdom. Susan Brown. Black Rose Books Ltd. ISBN pp. Social Forces. ISSN JSTOR Another humanist trend which cannot be ignored was the rebirth of individualism, which, developed by Greece and Rome to a remarkable degree, had been suppressed by the rise of a caste system in the later Roman Empire, by the Church and by feudalism in the Middle Ages. Humanism and Italian art were similar in giving paramount attention to human experience, both in its everyday immediacy and in its positive or negative extremes The human-centredness of Renaissance art, moreover, was not just a generalized endorsement of earthly experience.

Like the humanists, Italian artists stressed the autonomy and dignity of the individual. Journal of the History of Ideas. University of Pennsylvania Press. Izenberg 3 June Princeton University Press. Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion 1st ed. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN X. Symbols of Transformation: An analysis of the prelude to a case of schizophrenia Vol. Hull, Trans. Tate Modern. Archived 15 October at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 September Global Cultural Patterns". Cultural Evolution. Cambridge University Press. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. S2CID Mapping Differences". Freedom Rising. New York: Cambridge University Press.

PMC PMID Tuttle Co. Zalta, Edward N. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. American Economic Review. I mean by individualism the moral doctrine which, relying on no dogma, no tradition, no external determination, appeals only to the individual conscience. To say that the sovereignty of the individual is conditioned by Liberty is simply another way of saying that it is conditioned by itself. Pacific Institute for Public Policy Research, In Zalta, Edward N.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Political Ideology Today. Manchester University Press, OCLC Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool University Press, , p. Encyclopedia Corporation. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller. SUNY Press. Non Serviam. Oslo, Norway: Svein Olav Nyberg. Archived from the original PDF on 7 December Retrieved 1 September Karl Marx and the Anarchists.

Anarchism in Germany. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. Archived from the original PDF on February 4, Retrieved June 17, Muchos han visto en Thoreau a uno de los precursores del ecologismo y del anarquismo primitivista representado en la actualidad por Jonh Zerzan. Individualist Anarchism and Reaction". Su portavoz es L'Internazionale con sede en Ancona. The Bonnot Gang. Rebel Press, June The Freeman. Foundation for Economic Education. Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought Vol. Two Treatises of Government 10th ed. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved January 21, Is egoism morally defensible?