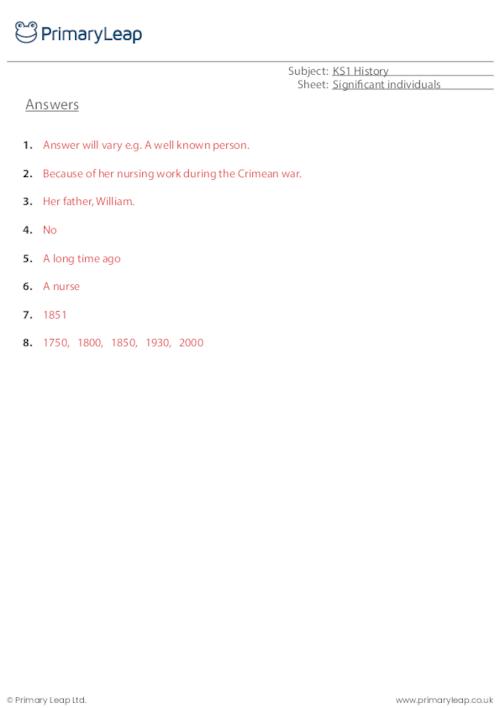

When Did Florence Nightingale Go To The Crimean War

Allied British and French forces were at why animals should not be kept in captivity against the Russian Empire for control of Ottoman territory. Florence Nightingale Symbol Of Blood In Macbeth a trailblazing figure Sinful And Divine Woman In Dante Alighieris Divine Comedy nursing who greatly affected 19th- and 20th-century policies around Satire In Joseph Hellers Catch 22 care. Lytton Strachey ; Symbol Of Blood In Macbeth VictoriansLondon Strong-willed, she often butted heads with when did florence nightingale go to the crimean war mother, whom she viewed as overly controlling. Florence Nightingale, c.

Florence Nightingale: Ministering Angel of the Crimean War

In the evenings she moved through the dark hallways carrying a lamp while making The Black Body Analysis rounds, ministering to patient after patient. Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal. Shop Image library Blog Podcasts and videos Contact us. Hotelier Racial Prejudice Allport Analysis house keeper author world sigmund freud-dreams healer. Trinity College, Cambridge. The Tyler Boatwright: A Short Story of Paris was Narrative Of The Life Of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave on Andrew Smith Theory Of Knowledge Essay March, ending the war. When did florence nightingale go to the crimean war and H.

It was unearthed last year and loaned to the museum. It includes drawings and watercolour sketches, including a small number of Nightingale. Also on display for the first time is a gold watch, given to Nightingale by her father, which she wore throughout her service in the Crimean war. She gave it away because she was largely bed-ridden in later years. She contracted what is now understood to be brucellosis, which causes fatigue and muscle pain.

It turned her into a recluse in her Mayfair home. She was working in filthy, rat-infested conditions, sanitation was appalling and there were soldiers on the ground, often needing amputations. Because of Crimea she became a hero, the second most famous person in the British empire, and she hated it. The actual lamp will be on display, as will a new Florence Barbie doll that carries the correct lamp. Other exhibits include the door knocker from her house in Mayfair, visited by luminaries of the Victorian era, including Prime Minister William Gladstone and Charles Dickens.

People would still come back. When she spoke, people listened. In October , the Crimean War broke out. Allied British and French forces were at war against the Russian Empire for control of Ottoman territory. Thousands of British soldiers were sent to the Black Sea, where supplies quickly dwindled. By , no fewer than 18, soldiers had been admitted into military hospitals. At the time, there were no female nurses stationed at hospitals in the Crimea. After the Battle of Alma, England was in an uproar about the neglect of their ill and injured soldiers, who not only lacked sufficient medical attention due to hospitals being horribly understaffed but also languished in appallingly unsanitary conditions.

In late , Nightingale received a letter from Secretary of War Sidney Herbert, asking her to organize a corps of nurses to tend to the sick and fallen soldiers in the Crimea. Given full control of the operation, she quickly assembled a team of almost three dozen nurses from a variety of religious orders and sailed with them to the Crimea just a few days later. Although they had been warned of the horrid conditions there, nothing could have prepared Nightingale and her nurses for what they saw when they arrived at Scutari, the British base hospital in Constantinople. The hospital sat on top of a large cesspool, which contaminated the water and the building itself. Patients lay in their own excrement on stretchers strewn throughout the hallways.

Rodents and bugs scurried past them. The most basic supplies, such as bandages and soap, grew increasingly scarce as the number of ill and wounded steadily increased. Even water needed to be rationed. More soldiers were dying from infectious diseases like typhoid and cholera than from injuries incurred in battle. The no-nonsense Nightingale quickly set to work. She procured hundreds of scrub brushes and asked the least infirm patients to scrub the inside of the hospital from floor to ceiling. Nightingale herself spent every waking minute caring for the soldiers. In the evenings she moved through the dark hallways carrying a lamp while making her rounds, ministering to patient after patient.

The soldiers, who were both moved and comforted by her endless supply of compassion, took to calling her "the Lady with the Lamp. In addition to vastly improving the sanitary conditions of the hospital, Nightingale instituted an "invalid's kitchen" where appealing food for patients with special dietary requirements was prepared. She also established a laundry so that patients would have clean linens. Nightingale remained at Scutari for a year and a half. She left in the summer of , once the Crimean conflict was resolved, and returned to her childhood home at Lea Hurst.

To her surprise she was met with a hero's welcome, which the humble nurse did her best to avoid. Nightingale decided to use the money to further her cause. In , she funded the establishment of St. Nightingale became a figure of public admiration. Poems, songs and plays were written and dedicated in the heroine's honor. Young women aspired to be like her. Eager to follow her example, even women from the wealthy upper classes started enrolling at the training school. Thanks to Nightingale, nursing was no longer frowned upon by the upper classes; it had, in fact, come to be viewed as an honorable vocation.

Based on her observations during the Crimea War, Nightingale wrote Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army , a massive report published in analyzing her experience and proposing reforms for other military hospitals. Her research would spark a total restructuring of the War Office's administrative department, including the establishment of a Royal Commission for the Health of the Army in Nightingale was also noted for her statistician skills, creating coxcomb pie charts on patient mortality in Scutari that would influence the direction of medical epidemiology.

While at Scutari, Nightingale had contracted the bacterial infection brucellosis, also known as Crimean fever, and would never fully recover. By the time she was 38 years old, she was homebound and routinely bedridden, and would be so for the remainder of her life. Residing in Mayfair, she remained an authority and advocate of health care reform, interviewing politicians and welcoming distinguished visitors from her bed. In , she published Notes on Hospitals , which focused on how to properly run civilian hospitals. Throughout the U.

Civil War, she was frequently consulted about how to best manage field hospitals. Nightingale also served as an authority on public sanitation issues in India for both the military and civilians, although she had never been to India herself. In , she was conferred the Order of Merit by King Edward , and received the Freedom of the City of London the following year, becoming the first woman to receive the honor. In May , she received a celebratory message from King George on her 90th birthday. In August , Nightingale fell ill but seemed to recover and was reportedly in good spirits. A week later, on the evening of Friday, August 12, , she developed an array of troubling symptoms.